transboundary diagnostic analysis of the

binational basin of the bermejo river

Binational Commission for the Development of the Upper

transboundary diagnostic analysis of the binational basin of the bermejo river

Bermejo River and Grande de Tarija River Basins

www.cbbermejo.org.ar

Global Environment Facility

www.gefweb.org

United Nations Environment Program

www.unep.org

Organization of the American States

www.oas.org

Binational Commission for the Development of the Upper

Bermejo and Grande de Tarija River Basins

www.cbbermejo.org.ar

Global Environment Facility

www.gefweb.org

United Nations Environment Programme

www.unep.org

Organization of American States

www.oas.org

TRANSBOUNDARY

DIAGNOSTIC ANALYSIS

FOR THE BINATIONAL BASIN

OF THE BERMEJO RIVER

FINAL VERSION

Republic of Argentina

Republic of Bolivia

MAY 2000

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. The Strategic Action Program for the Bermejo River Basin

1.2. Location and Political Structure

1.3. Contents of the Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis

1.3.1. Background

1.3.2. Structure of the Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis

1.4. The Environmental Profile of the Basin

1.4.1. Natural environment

1.4.2. Legal and institutional framework

1.4.3. Socioeconomic aspects

1.4.4. Environmental forecast of the Basin

2. ENVIRONMENTAL PROBLEMS AND TRANSBOUNDARY MANIFESTATIONS

2.1. Introduction

2.2. Characterization of the major environmental problems

2.2.1. Soil degradation. Intense erosion and desertification processes

2.2.2. Water scarcity and availability restrictions

2.2.3. Degradation of water quality

2.2.4. Destruction of habitats, loss of biodiversity and deterioration of

biotic resources

2.2.5. Conflicts from flooding and other natural disasters

2.2.6. Deteriorating human living conditions and loss of cultural

resources

2.3. Identification of Common Basic Causes

2.3.1. Inadequate political, legal and institutional framework

2.3.2. Poor planning and coordination between and within jurisdictions

2.3.3. Insufficient knowledge, commitment and participation by the

community and failure to encourage such participation

2.3.4. Inadequate financing and support mechanisms

2.3.5. Inadequate access to and application of sustainable technologies

2.4. Causal Chain

2.5. Synthesis of Environmental Problems

3. ENVIRONMENTAL PROBLEMS AND ITS RELATIONSHIP WITH STRATEGIC

ACTIONS

3.1. Introduction

3.2. Strategic Action Framework

3.3. Priority Environmental Problems, their Causes and Strategic Actions

3.4. Priority Actions, Scope of application and Basic Diagnostic Aspects

4. BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES PRODUCED BY THE SAP

5. LIST OF ACRONYMS

6. CARTOGRAPHIC FIGURES

Aspects of the natural environment

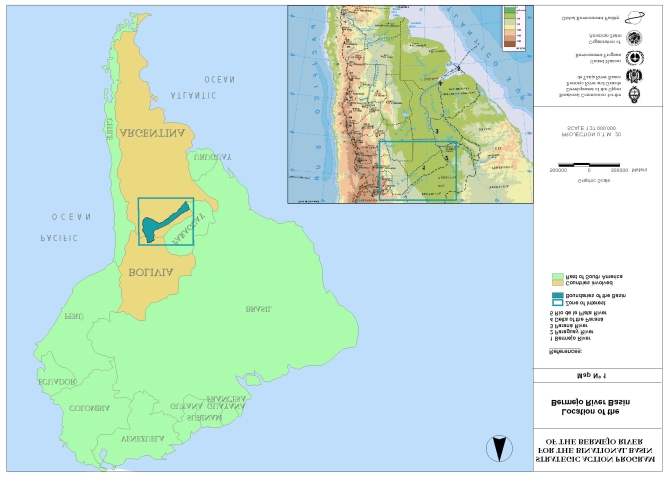

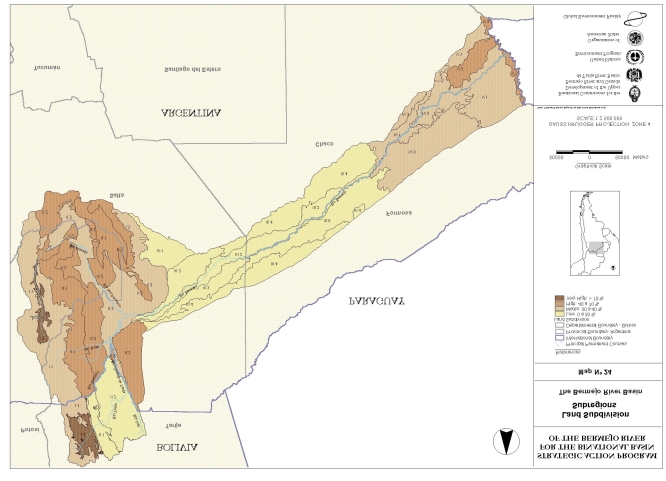

Figure Nº 1

Location of the Bermejo River Basin

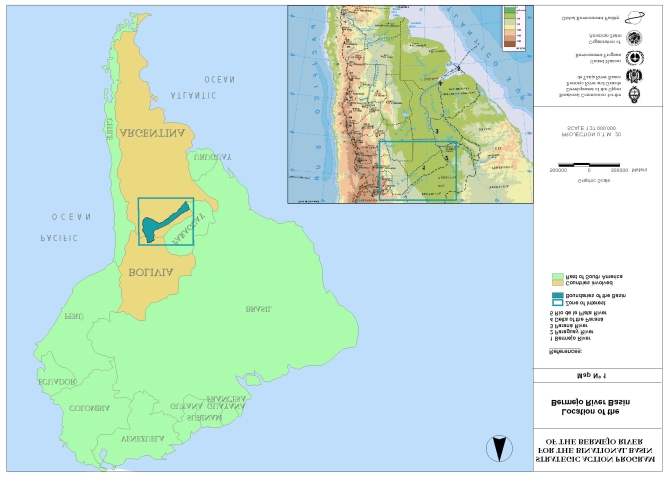

Figure Nº 2

The Bermejo River Basin

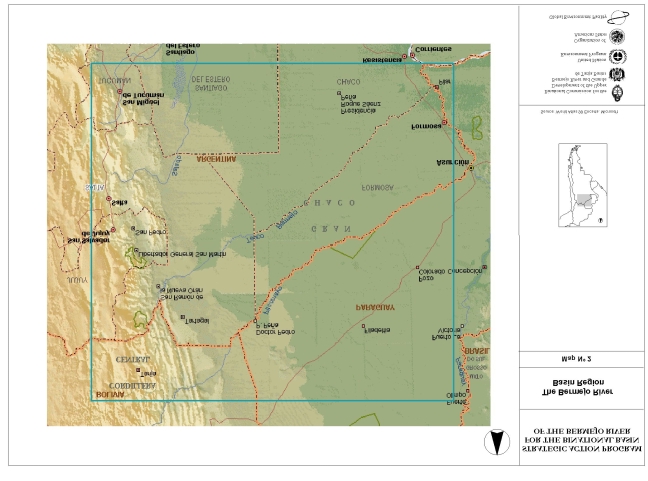

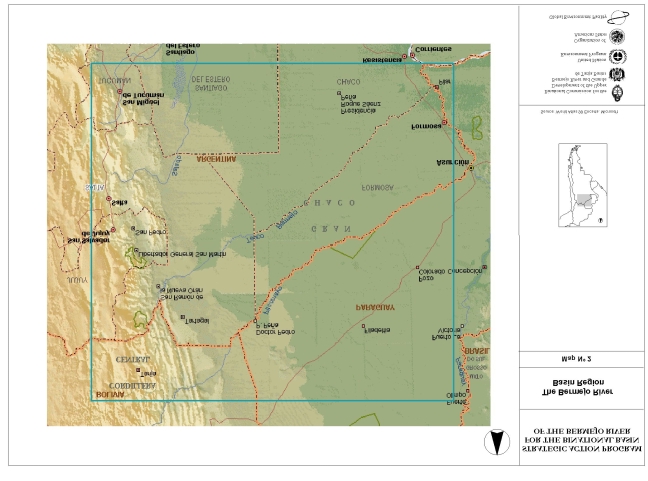

Figure Nº 3

Base Map

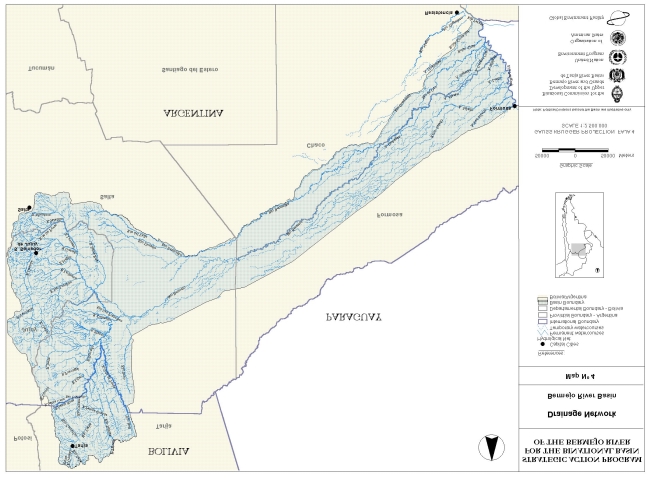

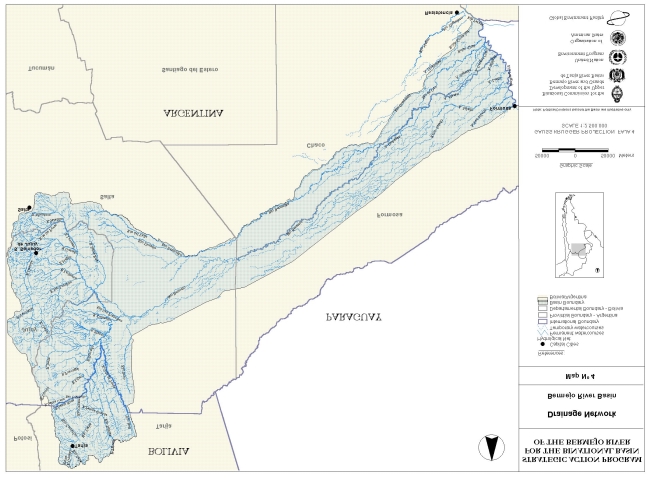

Figure Nº 4

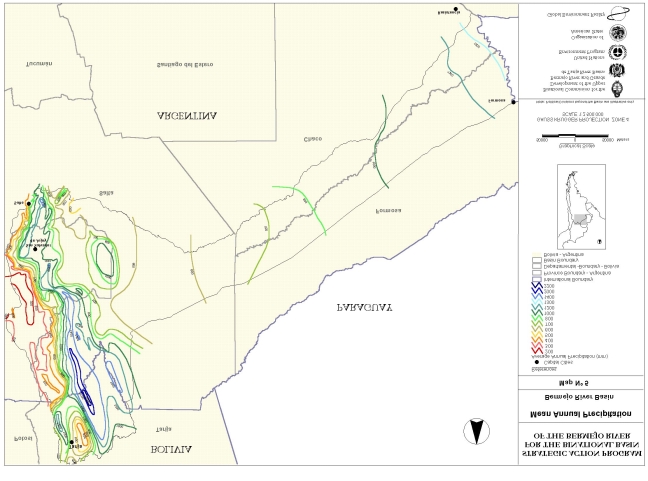

Hydrology

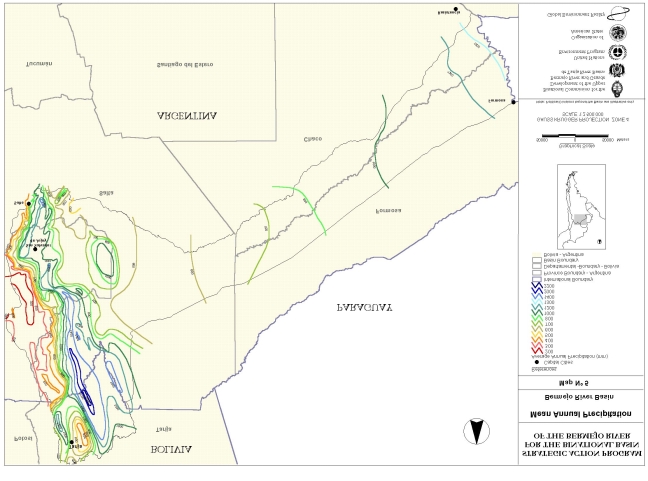

Figure Nº 5

Climate: Rainfall

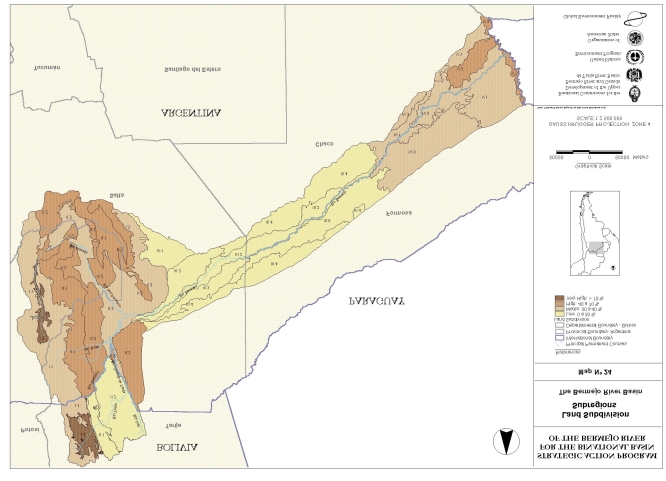

Figure Nº 6

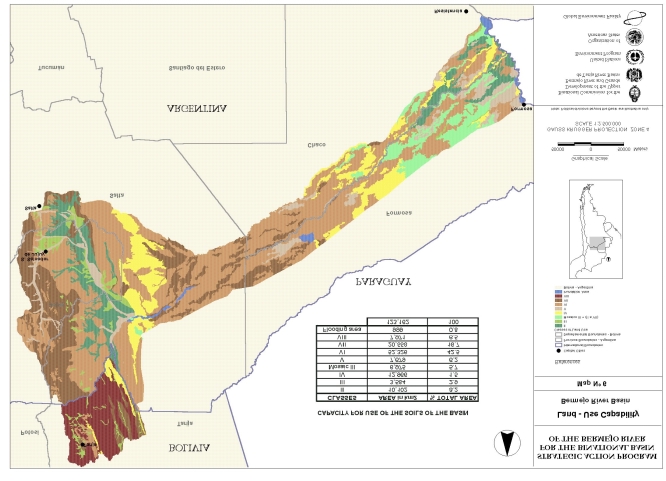

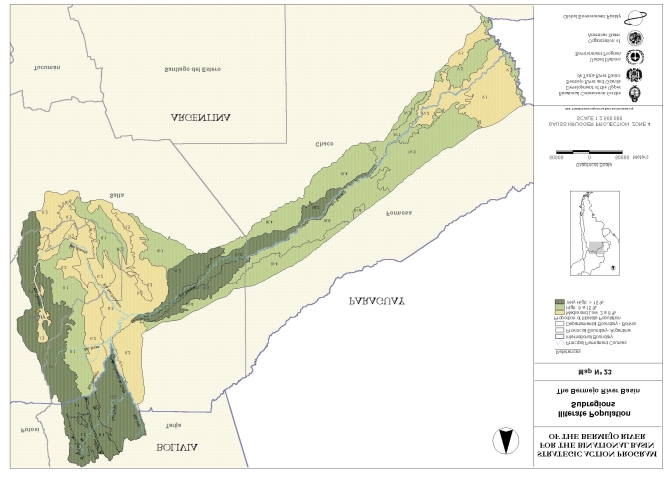

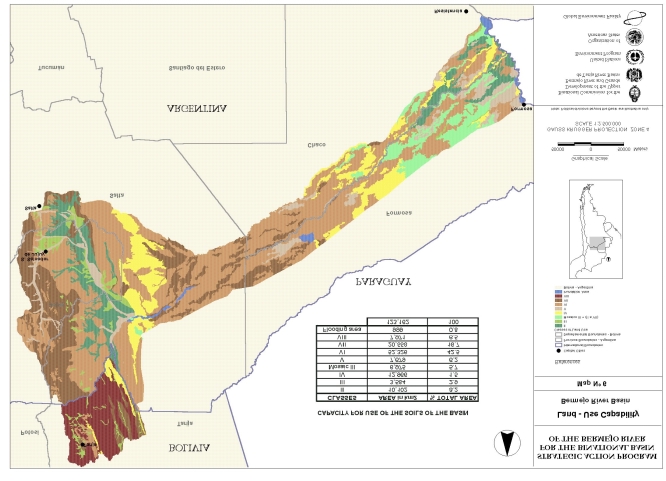

Soil Use Capacity

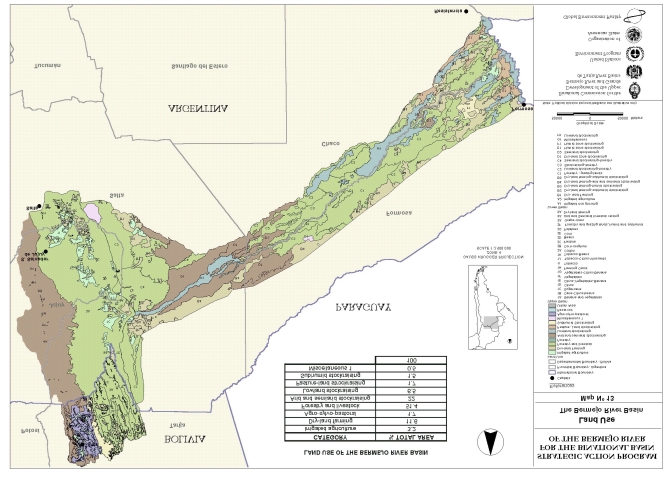

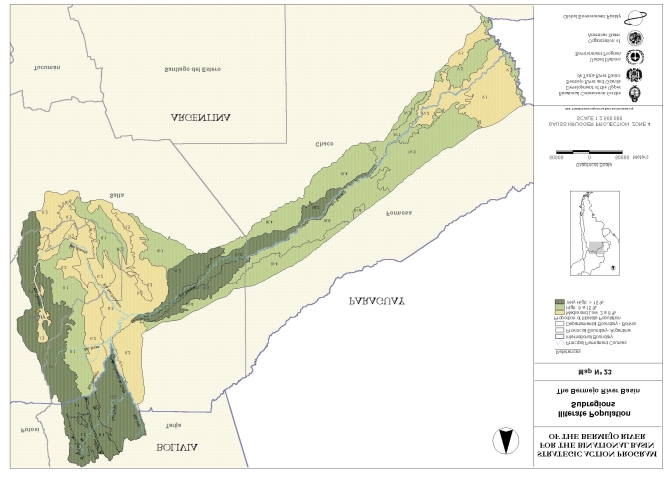

Figure Nº 7

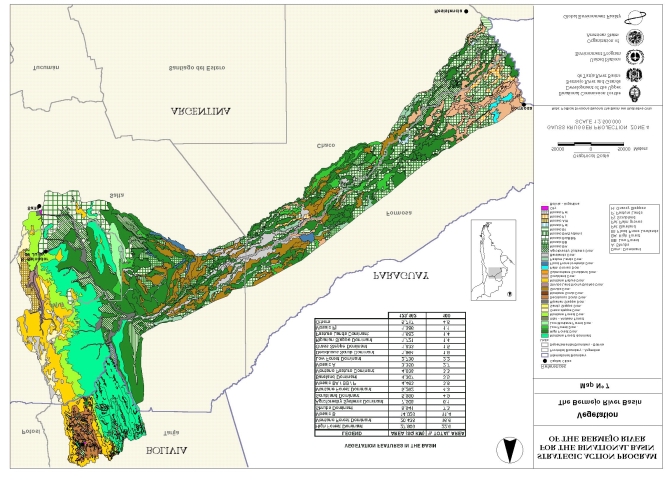

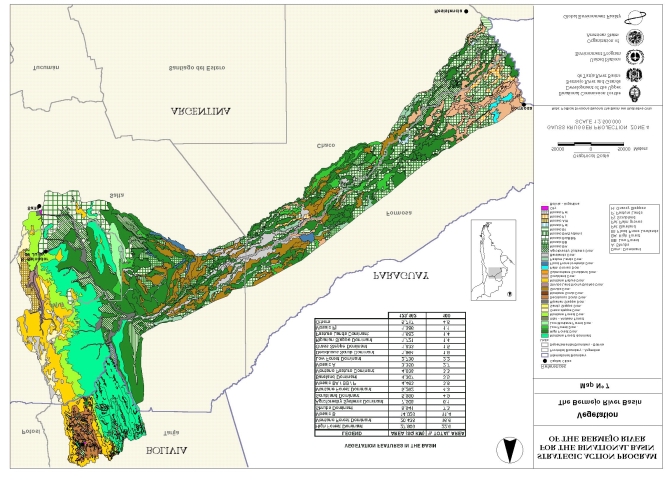

Vegetation

Figure Nº 8

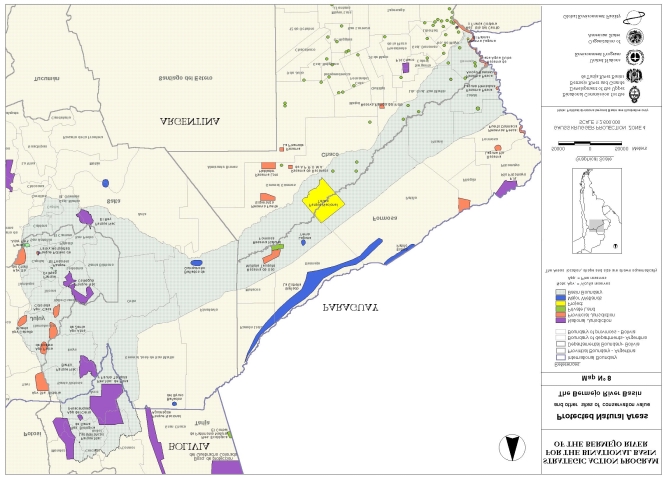

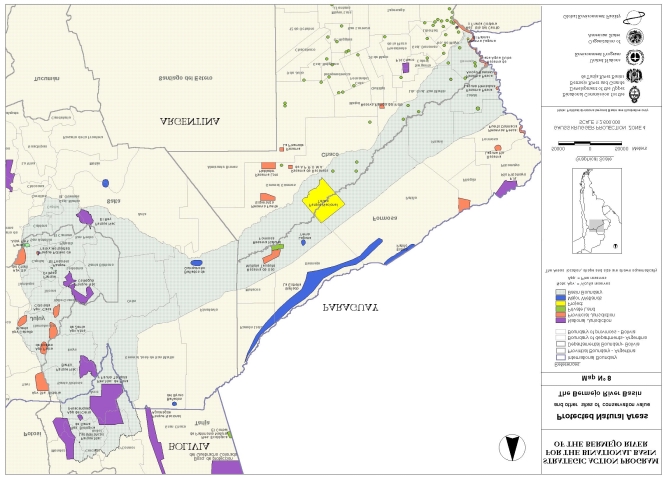

Nature Protected Areas

Figure Nº 9

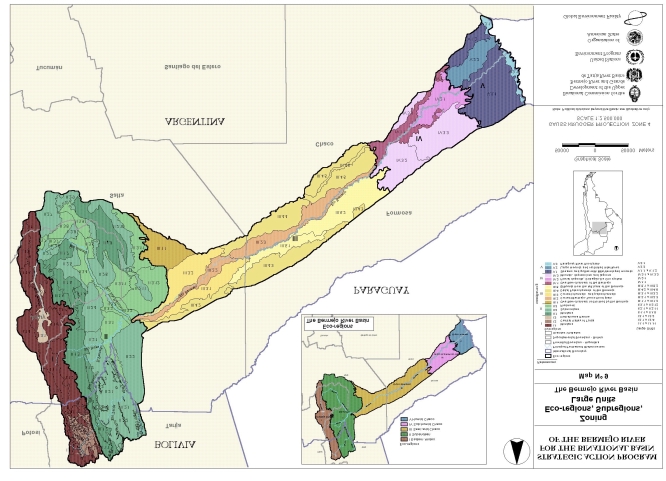

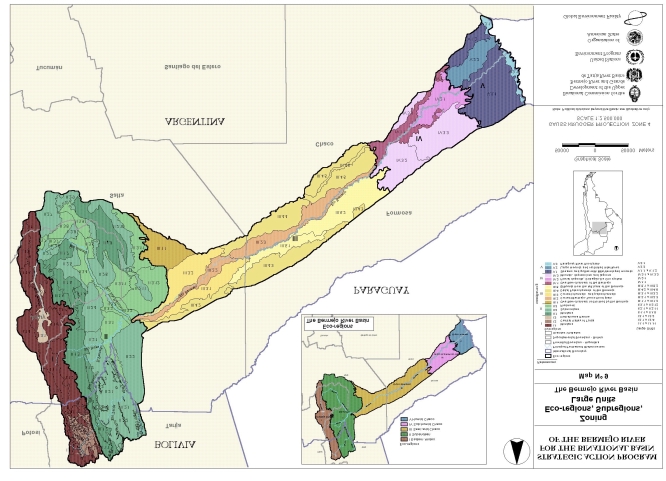

Eco-regions, Sub-regions, and Major Units

Socioeconomic aspects

Figure Nº 10

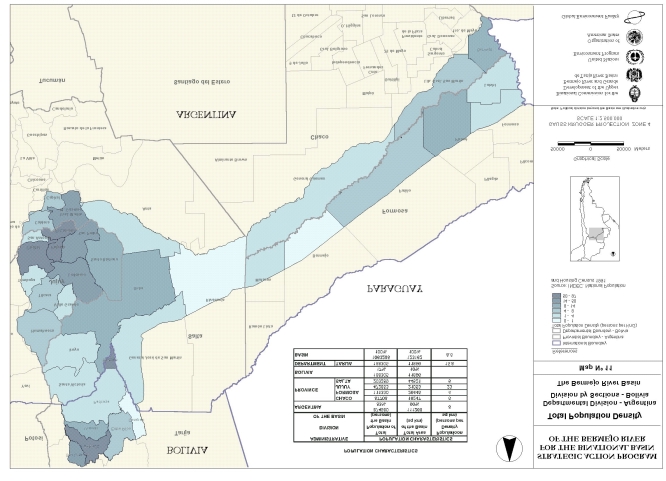

Political division

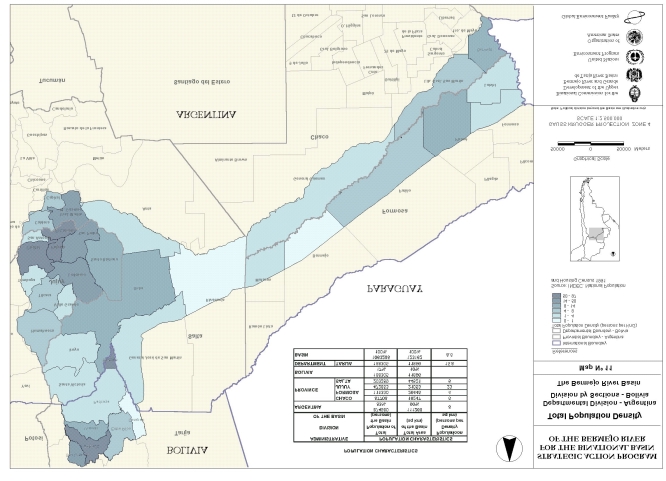

Figure Nº 11

Total population density

Figure Nº 12

Total population with basic needs unmet

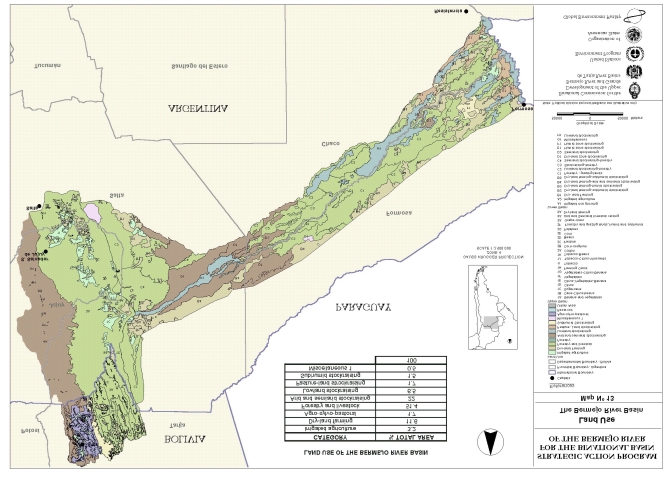

Figure Nº 13

Soil use

Figure Nº 14

Soil use with agroindustrial crops

Figure Nº 15

Generation of industrial jobs

Indicators of environmental problems at the level of the Major Units

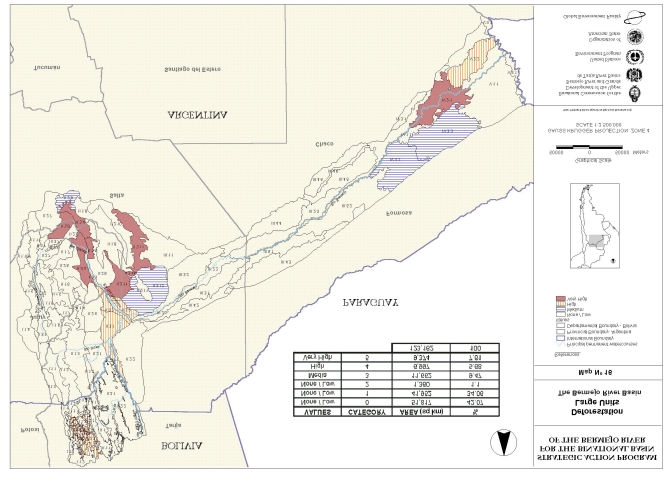

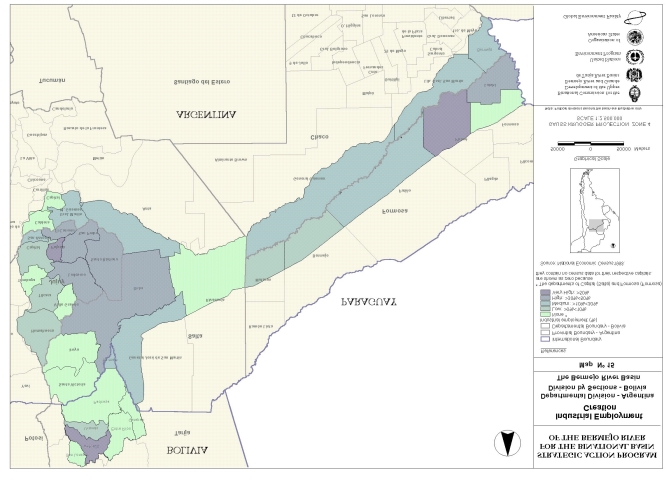

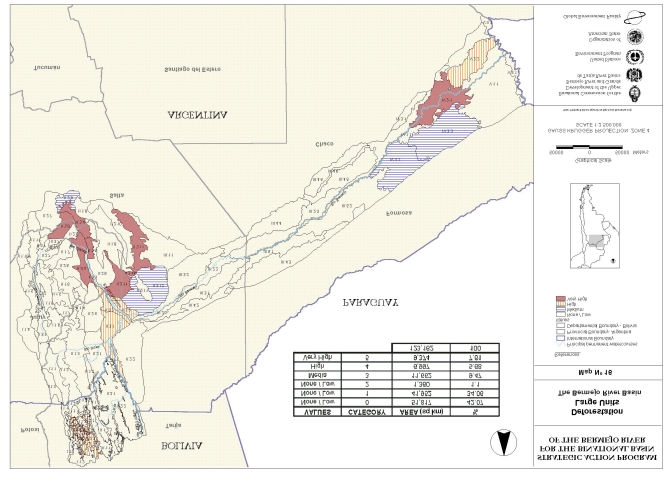

Figure Nº 16

Deforestation

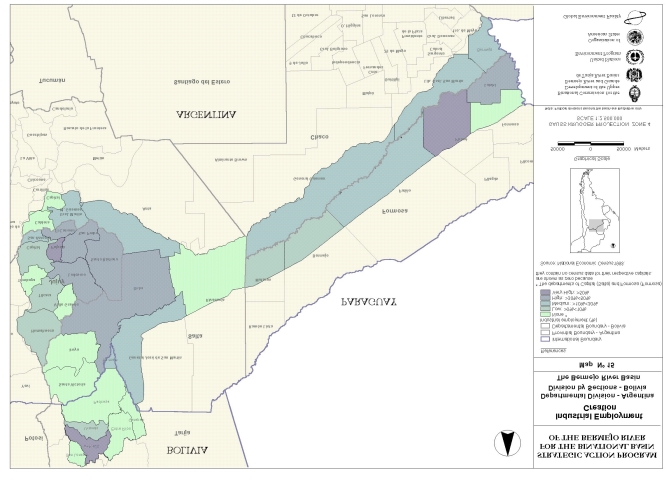

Figure Nº 17

Erosion

Figure Nº 18

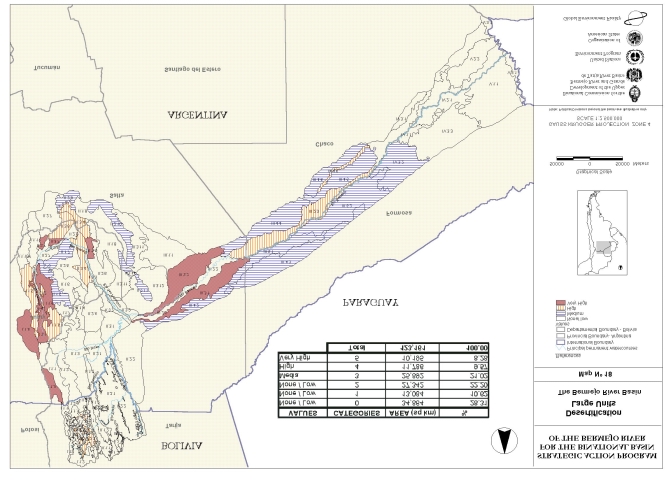

Desertification

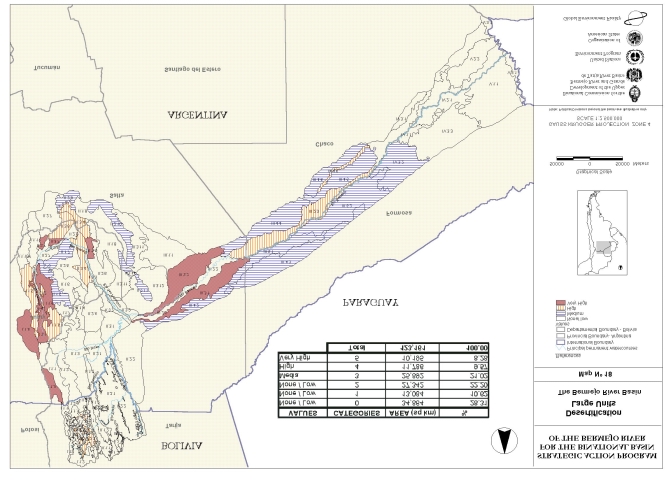

Figure Nº 19

Flooding and potential flooding

Figure Nº 20

Risk of loss of biodiversity

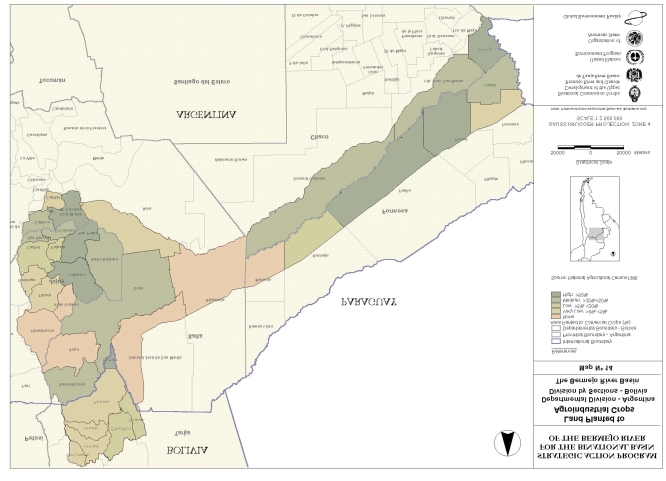

Figure Nº 21

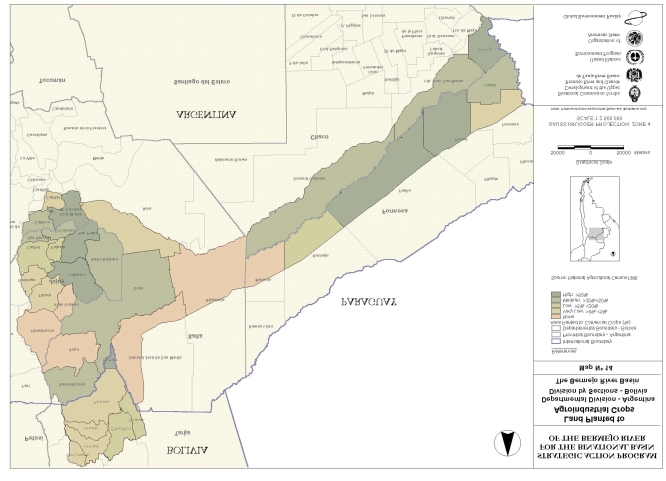

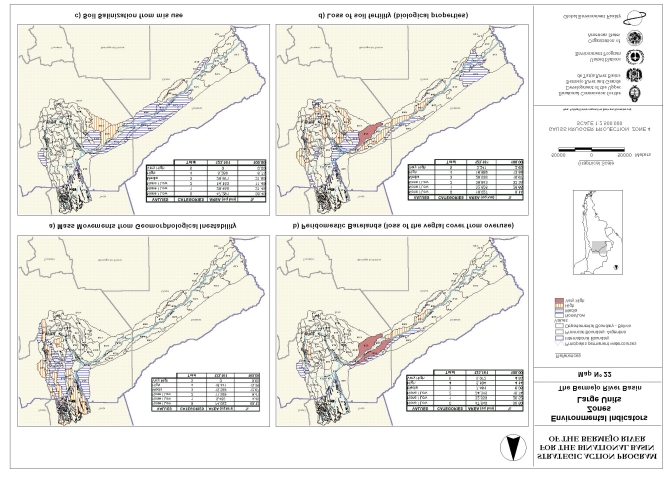

Indicators of environmental zoning

Figure Nº 22

Indicators of environmental zoning

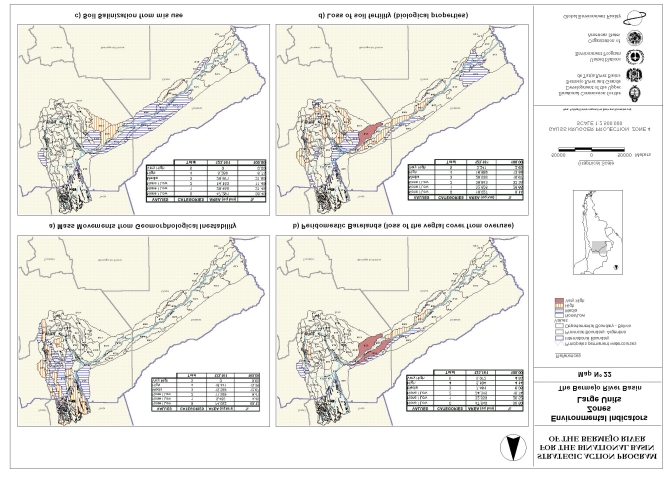

Indicators of environmental problems at the sub-regional level

Figure Nº 23

Illiterate population

Figure Nº 24

Subdivision of the land

7. ANNEXES

Annex I

SAP Work Elements

Annex II

Basic Environmental Information

Annex III Definition of Ecological Regions

Annex IV Environmental Zoning

Annex V

Quantification, location and assessment of Environmental Problems

2

INDEX OF TABLES

Table Nº 1

Territorial distribution of the Basin

Table N° 2

Population characteristics of the Basin. Estimated data

Table Nº 3

Total areas affected by soil degradation, erosion and desertification

Table Nº 4

Deforestation and threats to biodiversity

Table Nº 5

Nature Protected Areas

Table Nº 6

Size of Protected Areas, by Eco-region

Table N° 7

Number of endangered flora and fauna species by Eco-region

Table Nº 8

Conflicts from flooding and waterlogging, by Large Ecological Units

Table Nº 9

Geographic gross product of the Basin

Table Nº 10

Environmental Problems, symptoms, effects and transboundary

manifestations

Table Nº 11

Strategic Actions

Table Nº 12

Environmental Problems, Causes and Strategic Actions

Table Nº 13

Strategic Actions as they relate to fundamental concepts of the

Diagnosis

INDEX OF SKETCHES

Sketch N° 1 Methodological sketch: Identification of Causal Relationships

Sketch N° 2 Causal Relationship Chain for the Main Environmental Problems

3

1. INTRODUCTION

This Transboundary Diagnostic Analisys (TDA) is one of the principal results of the

Project to formulate a Strategic Action Program (SAP) for the Bermejo River Basin

and is intended to provide technical support and a strategic framework for that

Program.

1.1. The Strategic Action Program for the River Bermejo Basin

The Strategic Action for the Bermejo River Basin (SAP) was prepared as a joint effort

by the governments of Argentina and Bolivia, through the Binational Commission for

the Development of the Upper Bermejo River Basin and Grande de Tarija River Basins.

The work was carried out in both countries, beginning in August 1997, and was

completed in December 1999. The executing agency was the Organization of American

States (OAS), which is responsible for administering the funds supplied for the project

the Global Environment Facility (GEF) through the United Nations Environment

Program (UNEP).

The principal objective of the Strategic Action Program is to promote sustainable

development in the binational and inter-jurisdictional basin of the Bermejo River by: (i)

incorporating environmental concerns into the development policies, plans and

programs of the various jurisdictions, (ii) fostering an integrated management vision of

the basin and its natural resources, (iii) promoting the establishment of mechanisms for

regional articulation and coordination and public participation in consultation, through

(iv) implementation of programs, projects and actions that will (v) prevent or overcome

unsustainable use and environmental degradation of natural resources and (vi)

stimulate the adoption of sustainable practices for managing natural resources.

1.2. Location and Political Structure

The Bermejo River basin is located in the extreme southern portion of Bolivia, in the

department of Tarija, and in northern Argentina, where it embraces portions of the

provinces of Chaco, Formosa, Jujuy and Salta. Figure Nº 1 shows the location of the

basin with respect to the South American continent, and Figure Nº 2 shows its political

and administrative boundaries within the regional context.

The political and administrative structure in the two countries is different (Figure Nº

10). In Argentina, the system is that of a federal government, based on a confederation

of states known as Provinces. Bolivia has a centralized government system, under

which the country is divided into Departments.

The binational nature of the Bermejo River, and the federal system of organization

prevailing in Argentina, gives the basin an inter-jurisdictional character that makes the

institutional setting of this project particularly complex. The following levels of

government are involved:

Binational:

Binational Commission for Development of the Upper

Bermejo River and the Rio Grande the Tarija Basin

1

Regional:

Argentina:

Regional Commission for the Bermejo River1 (COREBE)1

Bolivia:

National Commission for the Pilcomayo and Bermejo

River (CONAPIBE)

Provincial level: Argentina:

Provinces of Chaco, Formosa, Jujuy and Salta

Departmental level: Bolivia: Department of Tarija

1.3. Contents of the Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis

1.3.1. Background

Preparation of a Transboundary Diagnosis was a specific objective of one of the three

major areas of work undertaken by the project to formulate the SAP, namely: (i)

transboundary diagnosis, (ii) public participation and pilot demonstrations projects, and

(iii) formulation of the Strategic Action Program. The work involved analysis of a local

and regional character, as well as sector studies, that served to update and supplement

the regional and transboundary diagnosis by addressing issues such as the generation

and transportation of sediments, water quality, environmental zoning, integrated water

resource management, the legal and institutional framework, and transboundary

migration, among others. As well, pilot demonstration projects were carried out in

different representative zones of the basin. On the basis of the studies and

consultations undertaken during the project, it was possible to incorporate additional

valuable information on various aspects (natural and social) of the basin, its major

regional and transboundary problems, their basic causes and the strategic areas for

action that make up this diagnosis and provide a foundation and context for the

Strategic Action Program.

In addition to generating information for the project itself, with the participation of more

than 30 institutions and more than 260 experts in different disciplines (Annex I lists the

completed SAP work elements. Chapter 4 of this report presents the documents and

reports produced by those Elements between 1997 and 1999) who helped in preparing

this environmental diagnosis, we drew upon available information from primary and

secondary sources and input from experts, government agencies and NGOs, including

the following, among others:

· A great number of sector and environmental studies, at the local or regional scale

throughout the Bermejo River basin, that have been produced over the last few

decades. Several bibliographic compilations, such as those produced in Argentina

in 1986 by the Federal Investment Council (CFI), with nearly 800 entries, and the

one produced by COREBE in 1991, are typical of the many efforts that have been

made at both the central and provincial level in this regard2. Similarly, the National

Commission for the Pilcomayo and Bermejo Rivers (CONAPIBE) and other

1 Federal agency created in Argentina by representatives of the national government, the riparian

provinces of Chaco, Formosa, Jujuy and Salta and the provinces of Santa Fe and Santiago del Estero.

2 Much background material was also compiled by central institutions such as the National Agricultural

Technology Institute, local universities and provincial agencies.

2

institutions in Bolivia have made an important effort to develop a greater

understanding of the basin.

· Among the studies, we wish to note in particular those that were produced with the

support of the Organization of American States on the Bermejo River (OAS 1971-

1973. Water Resources Study of BermejoRiver Basin) and La Plata River Basin

(OAS 1981. Río de la Plata: Basin; Study for the Planning and Development.

Bermejo River Basin. I Upper Basin; II Lower Basin), and those sponsored in

Argentina by COREBE, particularly those relating to the various stages and

components of the Study on the Development of Water Resources conducted

between 1993 and 1998, the latter within the context of the Binational Commission

for the Upper Bermejo River and the Rio Grande the Tarija Basin.

· Reports produced during the previous stage of preparation of the SAP project

(PDF Block B)3 condensing the most representative information from the various

background sources.

· The results and conclusions of the Workshops that were conducted in both

countries as part of the public participation program. In Argentina, there were three

workshops in the cities of Salta, Formosa and Jujuy (see bibliographic references

39, 40 and 41, in Chapter 4) and in Bolivia six seminars and workshops were held

in the city of Tarija, involving a total of more than 1000 participants.

Constant contact has been maintained with various stakeholders (governmental and

nongovernmental) in the basin. Through their various activities under the SAP, they

have contributed their knowledge and opinions on many different issues to this

diagnosis. Of special importance were the contributions to meetings of the

Governmental Working Group (GTG SAP)4 in Argentina.

1.3.2. Structure of the Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis

On the basis of existing knowledge about the basin (see in Chapter 4 the bibliography

generated by the various activities and work elements of the SAP between 1997 and

1999) a summary Environmental Profile has been prepared (an expanded version is

found in Annex II), covering the most significant aspects of the basin's natural

environment, its socioeconomic aspects and its legal and institutional setting. The

environmental characteristics are frequently geo-referenced in terms of a series of

Ecological Regions5 (Annexes II and III). This categorization identifies and delimits

homogeneous areas that are hierarchically related, as a tool for analyzing the principal

ecological processes and their associated environmental restrictions and conflicts. The

information provided by the various Work Elements (Annex I) makes it possible to

dimension and locate geographically the problems and symptoms that were detected

during the regional workshops in both countries.

3 PDF-Project Preparation and Development Facility, Block B

4 The Working Group in Argentina consisted of representatives of the provinces of Chaco, Formosa,

Jujuy and Salta, the Argentine delegation to the Binational Commission for the Upper Basin and

COREBE

5 The relationship between these Eco-regions and those identified in Dinerstein et al (1995) is explained in

Annex II.

3

The Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis (TDA) presents a characterization of the

environmental problems and their transboundary manifestations under the following

headings:

· Soil degradation. Intense erosion and desertification processes

· Water scarcity and availability restrictions.

· Degradation of water quality.

· Destruction of habitat, loss of biodiversity and deterioration of biotic resources.

· Conflicts from flooding and other natural disasters.

· Deteriorating human living conditions and loss of cultural resources

These major environmental problems show up in the water, the natural resources, the

land and the societies within the basin, as a consequence of various processes and

human activities, together with pre-existing or human-induced environmental

limitations. In other words, they reflect the approach to development and

environmental management followed in both the distant and recent past. These

problems now make themselves felt as constraints on sustainable development.

Each environmental problem has been analyzed on the basis of the following factors:

· Symptoms and Effects.

· Transboundary

Manifestations

· Direct

Causes.

· Common and Specific Basic Causes.

The most significant symptoms and effects are assessed by means of ecological and

socioeconomic indicators, either qualitative or quantitative, for dimensioning and

assessing the severity of the environmental problems identified in the Bermejo River

basin

Focusing on the watershed as the object of study and action, reveals more clearly the

trans-border manifestations of existing problems, acting through the dynamic

processes and components of the natural and social systems. The Bermejo river

crosses the border between Bolivia and Argentina, passes through 4 federal states of

the latter country and upon leaving the basin empties into the Paraguay River,

influencing downstream in the Paraguay-Parana system and the Rio de la Plata estuary

(shared by Argentina and Uruguay) (Figures 1, 2 and 10).

In turn, the explicit identification of these components underlines and confirms the need

to induce society to take a comprehensive vision of the basin as the starting point for

integrated and sustainable management of shared resources.

A series of causes have been identified and differentiated as the most significant

determinants of specific problems. Direct Causes are the immediate causes

determining the problem and are the result of a complex system of underlying factors;

they may be of natural as well as of human origin.

Basic Causes are the root causes or origin of the identified problems; they generate

4

the Direct Causes of human origin; therefore they are object of the interventions.

Taking in account the characteristics of the Bermejo river basin , the Basic Causes

were in turn divided into:

· Specific Basic Causes, defined in direct relation to each problem. The

intervention on this kind of causes contribute to the solution of the specific

problem.

· Common Basic Causes, are those of structural character originating in the

political, social, economic and institutional framework; they determine to various

degrees the existence of all the environmental problems and, therefore, they lye

at the origin of the chain of causal relationships. The interventions on this kind

of causes contribute to the solution of all the environmental problems.

During the various activities related to the SAP, and especially as a result of public

participation in the workshops held in both countries and meetings with the Government

Working Group in Argentina, a series of Strategic Action Areas, with their major

component Strategic Actions, were defined to respond to each of the environmental

problems identified. Table 13 offers a summary of the relationships between

environmental problems, causes and strategic actions.

Sketch Nº 1, methodologic framework, shows the relationships between the

environmental problems, their causes, the strategic actions and projects.

1.4. The environmental profile of the basin

This Binacional Basin (Figures Nº 1, 2 y 3), is characterized by the active and intense

interplay of hydrological, geomorphologic and ecological processes. It has significant

potential in terms of natural resources, the variety of its ecosystems and its biodiversity,

but is also subject to sharp constraints and environmental risks, biogeophysical as much

as social. In this context, the study identifies policy shortcomings and proposes

instruments for management and development that will take due account of the basin as

a whole.

1.4.1. The natural environment

The Bermejo river basin, shared by Argentina and Bolivia (Figure Nº 4), is an important

part of the macro-region of the del Plata Basin. It embraces a surface area of 123,162

km2 (Table Nº 1) and its principal watercourse has a length of more than 1,300 km.

Because of its characteristics it is divided into the Upper Basin (Superior) and the Lower

Basin (Inferior).

In Bolivia, the upper basin of the Bermejo is located entirely in the Department of Tarija.

The remainder of the upper basin, and all of the lower basin, is located in Argentina. The

hydrographic system is formed by four major tributaries: the Grande de Tarija River, the

Upper Bermejo River, which after Juntas de San Antonio is known as the Bermejo, the

Pescado River and the San Francisco River.

Of the surface area of the basin, 50,191 km2 belongs to the upper basin (shared by

both countries) and 72,971 km2 in the lower basin (entirely within Argentina).

5

Sketch N° 1 METHODOLOGICAL SKETCH: IDENTIFICATION OF CAUSAL RELATIONSHIPS

EFFECTS

AND

TRANSBOUNDARY

SYMPTOMS

MANIFESTATIONS

S

T

R

A

ENVIRONMENTAL

T

PROBLEMS

P

E

R

G

O

I

J

C

E

C

A

T

C

S

DIRECT CAUSES

T

I

O

N

SPECIFIC BASIC

COMMON BASIC

S

CAUSES

CAUSES

TDA

SAP

Represents the intervention of SAP on the Basics and Directs Causes. SAP actions will results in the mitigation of the

environmental problems and their consequences.

6

Table Nº 1

TERRITORIAL DISTRIBUTION OF THE BASIN

JURISDICTION

AREA (km2)

PROPORTION(%)

COUNTRY

BOLIVIA

11,896

10

Department

Tarija

11,896

10

COUNTRY

ARGENTINA

111,266

90

Provinces

Chaco

19,247

16

Formosa

26,445

21

Jujuy

21,053

17

Salta

44,521

36

TOTAL

123,162

100

Environmental information on the basin was integrated and synthetized on the basis of

a series of Ecological Regions (31), which provided the geographic basis for analyzing

a set of natural and socioeconomic indicators and their associated constraints. The

territory was divided into hierarchically related spatial units, on the basis of different

natural attributes, homogenous at each level of detail. This work relied essentially on

the Thematic Mapping (1, 13 and Figure Nº 9) generated through the interpretation of

satellite images and other information sources. In this way 5 Eco-regions, 17

Subregions and 68 Large Ecological Units were identified, as listed in Table Nº 15 of

Annex II.

From the viewpoint of its Geology, three large structural units may be identified in the

Basin: the Eastern Range of the Andes (Eastern Andes), the Subandean Ridge and the

Chaco Plain. In Bolivian the first unit is reflected in the ranges of Sama and Condor,

which border the central valley of Tarija reaching heights of 3,000 to 4,600 meters

respectively. The Central Valley bottom is formed by a fluvio-lacustrine plain. In

Argentina, there is the Santa Victoria Sierra, which in the south is divided by the

Quebrada de Humahuaca. It is a rugged, rocky range with maximum elevations of

6,200 m a.s.l like in Chani mountain. The Sub-Andean ridge, which has the Eastern

Andes on the west and the Chaco Plain on the east, are formed mainly by narrow

extended parallel ranges running in a north-south direction with an elevation of about

2,000 m.a.s.l. Lastly, the Chaco Plain, where the Lower Basin is located, presents a

relief associated mainly to fluviomorpholigical dynamics.

From the viewpoint of its Geomorphology, the region has sectors that are very active

in generating sediments, and these affect large areas, especially in the upper basin.

Simulation models were applied to estimate the rate of sediment generation through

surface erosion (Figure I of Annex II). Figure II of that Annex shows in qualitative

terms the areas that are most susceptible to the generation of mass-movement

processes in the upper basin. Such processes not only contribute greatly to the

creation of sediments but also constitute a natural hazard for the local population, many

of whom are highly socially vulnerable. The major volume of material mobilized in the

6

upper basin is carried by the river system into the lower basin, where the plain serves

as the principal receptor for medium and course material, while the finer sediment is

transported downstream out of the basin.

The study of transboundary sediment transport was a focus of interest of the TDA in

both countries (2 and 14). In terms of sediment production per unit area, the San

Francisco river carries about 700 t/km2 year and the Bermejo river about 3,050 t/km2

year upstream of the confluence with said river. Bermejo basin comprises sub basins

with highly variable sediment production; for example, 1,400 and 1,700 t/km2 year the

Grande de Tarija and Bermejo sub basins respectively, upstream of the Juntas de San

Antonio junction and over 14,800 t/km2 year the Iruya river subbasin up to El Angosto.

It is estimated that on average about 100 million tons of suspended sediment a year

are carried from the Bermejo river into the Paraguay-Parana system. The National

Water and Environment Institute of Argentina (2 and 14) and other specialists (3)

analyzed the incidence of sediments carried by the Bermejo river in shaping the Delta

of the Parana and the Rio de la Plata. The studies indicate that the contribution of sand

from the Bermejo river to the Paraguay-Parana Rivers is not significant. On the other

hand, silt and clay constitute 90 percent of suspended sediments carried by the

Parana, which are deposited primarily in the Rio de la Plata. The annual amount of fine

materials (silt and clay) dredged from the navigation channels in the Rio de la Plata is

equal to 23 percent of the total contribution of the Bermejo River.

The climate presents a sharp rainfall gradient (1), from 2,200 to 200 mm annually

(Figure Nº 5), and large portions of the territory suffer water shortages, including

periods of extreme precipitation and drought (Figure III of Annex II).

The hydrology of the rivers is rain-controlled, with sharply defined seasonal variations:

volumes are highest during the rainy season (January to March, which accounts for up

to 75% of annual flow (it amounts up to 85% considering the whole summer period),

and are lowest during the dry season (April to September).

The mean discharge of the Upper Bermejo river at Aguas Blancas is about 92 m3/s and

that of the Grande de Tarija river at Algarrobito-San Telmo reaches 127 m3/s, with

specific discharges ranging between 18 and 12 l/s.km2, respectively. Thus the mean

annual discharge at the Juntas de San Antonio junction amounts to 219 m3/s. After the

confluence of Pescado river, the average flow is 347 m3/s escalating to 448 m3/s

downstream of the junction of the Bermejo with San Francisco river, which constitutes

the contribution of the Upper into the Lower Basin. The average specific flow of the

various rivers in the Basin ranges between 2.0 and 30 l/s.km2.

The scale of these basins and the heterogeneity of their environmental conditions, and

especially their use, produces wide variations in water quality: some stretches are unfit

for human consumption, because of bacteriological contamination, the discharge of

semi-treated or raw urban sewage, the dumping of industrial wastewater, or excess

salinity (Tables Nº 2 and 3 of Annex II)

The physiography, genesis, climate and fluvial shaping, among other factors forming

the soil, have generated a high degree of taxonomic heterogeneity of soils, which also

shows up in their capacity for use (Figure 6). Against this variability, there is a wide

7

diversity of uses, current and past, that have determined a mosaic of conditions from

the viewpoint of soil conservation. Table 5, in Annex II, shows the relative importance

of each class of soil use capacity. It highlights the absence (at the working scale

adopted) of soils of class I, which have the greatest agricultural potential (no limitations

on use), and the dominance of soils of class VI (42 percent), which present severe

limitations and are generally not suitable for growing crops. Only 27.3 percent of the

surface area of the basin has soils of class II to IV.

The heterogeneity of environment, climate and relief makes itself felt in a great diversity

of biomes and vegetation physiognomies (Figure 7 and Tables Nº 6 and 7 of Annex

II). The dominant typologies in the basin, accounting for more than 47 percent (58,186

km2) of the surface, are forests and rainforests, which include montane and piedmont

cloud forests, dry forests, sub-humid or humid forests, evergreen forests, semi-

deciduous or deciduous forests, accompanied by grasslands, shrubby and grass

steppes.

The principal risk factors for wildlife fauna are modifications to habitat, especially

through deforestation (massive or selective), and the advancing agricultural frontier. In

some cases of species with economic value, legal or illegal hunting has been an

important source of pressure. Table Nº 8 of Annex II shows the number of species of

reptiles, birds and mammals at varying degrees of conservation risk. It will be noted

that the Sub-Andean and the Sub-Humid Chaco and Humid Chaco Eco-regions are

those where said risks are relatively highest. Mammals are the group at greatest risk.

Conservation of Natural Heritage is examined from three complementary points of

view: Nature Protected Areas, Wetlands, and Biodiversity. Both countries have special

provisions for land use in Nature Protected Areas (NPA), although within different legal

frameworks (24 y 25). Table Nº 9 of Annex II contains full information on those NPAs

that are wholly or partially included in the basin, NPAs in surrounding areas, and

wetlands of importance from conservation viewpoint. Considering the basin as a whole,

6489 km2 is under some form of conservation cathegory, representing more than five

percent of the total area. While the number of these areas throughout the basin, and

the surface area in the Bolivian sector, are numerically important indicators, the

protection of biodiversity and natural heritage is not assured. This reflects the fact that

these NPAs are not fully representative in terms of bio-geography, there is discontinuity

of habitats and ecological corridors, frequent occupancy with incompatible uses, and an

insufficient degree of control and surveillance.

The Bermejo River basin, thanks to its hydrographic network and associated wetlands,

acts as a complex system of bio-geographic corridors connecting, from west to east,

the ecosystems of the Eastern Andes and the Yungas with the ecosystems of the

Chaco and the Paraguay-Parana.

1.4.2. Legal and Institutional Framework

The political and administrative structure (Figure 10) of Argentina is federal, based on

a confederation of provinces subdivided into departments, within which the

municipalities are defined. From the political and administrative viewpoint, Bolivia is a

centralized country, structured into Departments, formed territorially by the integration

8

of Provinces which are divided into Municipalities.

The strengths and weaknesses of this political and institutional framework are dealt

with in detail by studies (24 y 25). The legal framework in both countries is shown in a

simplified form in Table 10, Annex II.

1.4.3. Socioeconomic aspects

The socioeconomic aspects of the basin have been analyzed in the following studies

listed in the bibliography in Chapter 4: (6, 10, 12, 19, 20, 27, 28, 29, 30, 33, 36 y 37).

The total population of the basin was 1,063,285 inhabitants, according to the most

recent census data available, and is estimated at about 1,200,000 at the end of 1999. It

is distributed heterogeneously, including both heavily populated areas and relatively

empty spaces. The total population of the Argentine sector is 874,980, according to the

1991 Census, and that of the Bolivian sector is 188,305 according to the 1992 Census

(Table Nº 2 and Figure Nº 11). For the basin as a whole (Figure Nº 12), about 41

percent of the population suffers from Unmet Basic Needs (UBN), illustrative of the

high poverty level in the region.

Illiteracy amounts to about 9.9 percent among the total population (older than 10 years

for Argentina, and older than 15 years for Bolivia). The proportion of the population

without health coverage in the Argentine provinces was 53 percent; these people are

dependent on public health services. The same indicator reaches 37 percent in Tarija.

This indicator reflects critical conditions from the socioeconomic viewpoint in major

sectors of the population, conditions that become even more acute in certain sectors of

both Argentina and Bolivia.

An analysis of major social indicators, carried out with the studies indicated in the

bibliography (10, 28, 29, 33 y 37), shows that in much of the basin living conditions are

extremely precarious for a large portion of the population.

The socioeconomic changes that have occurred in recent decades have accentuated

the vulnerability of broad sectors of the population, and of their economic livelihood, in

the face of natural threats such as floods, landslides, and drought and other extreme

climatic events.

Land use, in relation to economic activities, is shown in Table Nº 12 of Annex II and in

Figure Nº 13. Extensive agricultural uses dominate, covering about 14 percent of the

total area. Figure Nº 24 shows a high degree of land subdivision in the upper basin,

and in a band that includes the provinces of Salta, Chaco and Formosa in Argentina.

The area occupied by agro-industrial crops (sugar cane, cotton, tobacco and others) is

still relatively restricted, as can be seen in Figure Nº 14, but has been growing in

recent years. Figure Nº 15 shows values for industrial employment, which are high in

only a few areas of the basin. Table Nº 14 of Annex II describes these aspects in

further detail.

9

TABLE N° 2

POPULATION CHARACTERISTICS OF THE BASIN: ESTIMATED DATA

POPULATION CHARACTERISTICS

POPULATION

UNMET BASIC NEEDS

ILLITERACY

OF THE BASIN

DISTRIBUTION IN THE

(UBN) IN THE BASIN

BASIN

IN THE BASIN

POLITICAL/

Total

Total

Total

ADMINISTRATIVE

Total

Populati

Total

surface

Rural

Populatio

Rural

Ratio to

DIVISION

Population

on

Rural

IN THE BASIN

area of

Population

n with

Population school-age

of Basin

Density Population

Basin

Density

UBN

with UBN

population

(Persons)

P/km2

(persons)

km2

P/km2

48,449*

37% of

65.6% of

874,980

111,266

illiterate

ARGENTINA

(83%)

216,977

total

rural

90%

8

24.8 %

1.9

population

7.5%

population

PROVINCE CHACO

87,708

19,247

5

37,583

1.9

53%

66%

17.9%

FORMOSA

111,330

26,445

4

42,474

1.6

37%

60%

8.0%

JUJUY

472,653

21,053

71,397

3.4

34%

59%

6.3%

24

SALTA

203,289

44,521

5

65,523

1.5

35%

70%

6.5%

64.1% of

90.2% of

188,305

11,896

74,967

BOLIVIA

total

rural

18.5%**

(17%)

10%

15.8

39.8%

6.3

population population

DEPART

34,836

TARIJA

188,305

11,896

15.8

74,967

6.3

64.1%

90.2%

MENT

illiterate

1,063,285

123,162

41.7 % of

73.5%

BINATIONAL

291,944

total

of rural

BASIN

8.6

27.5%

2.4

9.9%

100%

100%

population population

References: * % of illiterate population, in Argentina, older than 10 years

** % of illiterate population, in Bolivia, older than 15 years

10

Socioeconomic conditions in the basin have historically led to transboundary migration. In the

sub-basin of the Bermejo River within Bolivia, 42 percent of the population surveyed (rural

population) had left at some time for Argentina. Of these, 69.9 percent declared as their reason

the search for work, in most cases related with agriculture. Nevertheless, such migrations

appear to have little impact on natural resources and infrastructure in destination areas within

the Argentine portion of the basin, when compared with the pressures of the local population

and migratory movements within Argentina.

Broad sectors of the basin have a precarious economic existence (32, 36, 37). While in many

cases output has been growing, farming has been expanding, and exports have been rising

during the 1990s, these figures have not translated into improved welfare of the population.

Gross income is growing but is not being redistributed, compounded by the fact that Argentina

has suffered a steady deterioration of its fiscal situation, which has left provincial governments

short of financial resources.

The high degree of social vulnerability identified within the basin and its region makes it

essential to strengthen the institutional framework and the organization of the various sectors of

civil society.

1.4.5 Environmental forecast on the Basin

The predictable scenarios for the region´s future (32) show at present the existence of weak

markets in the context of a restricted supply of and demand for natural resources, and of a

society generally characterized by extensive poverty in which economic and social processes

falter and the natural and human habitat is degraded. This undeniably indicates vulnerability,

both environmental and social, upon which the effects of MERCOSUR and world-wide economic

globalization become apparent.

Therefore, the probable scenario is that:

· Local and regional stakeholders will continue to show a lack of vision, understanding,

and sense of belonging to the Basin.

· Regional and local planning remains insufficient, preventing development agents from

acting on the real needs of society.

· The perception and management of the natural resources, particularly water, will remain

fragmented. An understanding of the real potentialities and restrictions of natural

resources is still incomplete or insufficient.

· Unsustainable practices will still predominate. The complex diversity of the various

natural and social environments that make up the region will not be sufficiently taken into

account. An assessment of competitiveness, both between and within regions, remains

uncompleted.

· Environmental degradation will increase and the problems identified will worsen,

especially those related to the production and transport of sediments, water pollution,

and soil capacity. Low productivity continues to affect the income of the inhabitants,

particularly the indigenous communities and small farmers, thus exacerbating the non-

sustainable extractive use of resources, deforestation, and the expansion of the

agricultural frontier. The pressure on high-risk areas in terms of erosion, sediment

production, and damage to biodiversity conservation will increase.

· The impacts of productive activities and large infrastructure projects will be perceived in

11

fragments and mainly not until after their implementation. The announcement of projects

will generate migratory movements from "push" areas within and beyond the basin.

Interregional migratory movements will increase and change direction, which may affect

production and the use of natural resources in rural areas, depending upon the timing

and stages of the projects. According to the forecast, this process will have no possibility

of changing the present socioeconomic framework significantly, owing to the lack of a

planning process capable of mitigating the negative effects.

· Individual expectations of improving the relative position of the various micro-regions, in

particular of those better positioned, will hamper attempts at regional and basin-wide

integration.

· Attention to productive activities and the improvement of living conditions will remain

limited to welfare actions undertaken by national and local governments, international

organizations, etc.

· The strengthening of municipalities and grassroots organizations may remain limited to

occasional support from various levels, which may even weaken them and create even

greater anarchy in local government or an increase in dependency and political

partisanship.

· Lack of regulation will intensify some problems with large agricultural corporations

usually from outside the region and without links to local culturewhose impact, although

temporarily benefitial, may deepen imbalances within the region and enhance

vulnerability, social as well as environmental.

· The government will keep a regulatory rol of medium intensity. Projects will develop

inorganically and land will be put into production without a proper assessment of their

environmental capacities and constraints, awarding ownership, orderly procedures for or

consideration of the characteristics of the beneficiaries.

· Less- favoured communities will remain physically and socially isolated and localized

conflicts between interests from outside the region for the control and management of

resources may arise.

· Nature protected areas and other heritage sites may become at risk in the contact zone

with the areas where projects will be carried out, giving rise to conflicts with

environmental groups and/or those that are traditionally oriented to a harmonious

relation between nature and society.

The present situation is characterized by a lack of equity for the various social sectors and by an

insufficient response to the threats to which the communities, their environment, and the

associated water resources are exposed. If the situation remains unchanged, it will become

impossible to achieve objectives of sustainable development; at the same time, the

environmental degradation and social vulnerability in the Bermejo River Basin identified in this

TDA, will be aggravated.

12

2. ENVIRONMENTAL PROBLEMS AND TRANSBOUNDARY MANIFESTATIONS

2.1. Introduction

A basin of the scale and complexity of the Bermejo River will suffer from many environmental

problems that make themselves felt in different forms and degrees of intensity. To identify and

evaluate these problems, information was drawn from various sources, in particular from the

different SAP Work Elements and the inputs from the various participation mechanisms. The

division of the basin into ecological regions (31) provided a comprehensive overview, in which

context the most significant and critical environmental problems were examinated, particularly

those associated with significant problems or conflicts over water and natural resources in the

Basin, which have transboundary manifestations.

The analysis and synthesis of environmental problem indicators was conducted at the scale of

Large Units and Subregions (Annex III and Figure Nº 9), shown in geographic terms in Figures

Nº 16 and 22.

These indicators were discussed at regional workshops of the SAP, in Jujuy (December 1998)

and in Tarija (May 1999) (39, 40 and 41), as well as at Working Group meetings. These

problems are:

· Soil degradation. Intense erosion and desertification processes

· Water scarcity and availability restrictions

· Degradation of water quality

· Destruction of habitats, loss of biodiversity and deterioration of biotic resources

· Conflicts from flooding and other natural disasters

· Deteriorating human living conditions and loss of cultural resources

2.2. Characterization of the principal environmental problems

Characterization of environmental problems was carried out by identifying their symptoms and

effects, transboundary manifestations, and main causes. Sketch Nº 2, at the end of the chapter,

shows the causal chain relationships of said environmental problems. Table Nº 10 describes the

environmental problems in terms of their effects, symptoms and transboundary manifestations.

Annex V summarizes the quantitative, geographical and weighting aspects.

2.2.1. Soil degradation. Intense erosion and desertification processes

The symptoms and effects of soil degradation as a result of intensive processes of erosion and

desertification make themselves felt in the destruction of the soil's natural productive capacity,

the reduction in the quality and quantity of agricultural output, the loss of productive areas, the

degradation of water quality, the loss of organic material and nutrients in the soil, as a result of

the decline or loss of vegetation cover, compacting of the soil, thereby reducing its water-

retention capacity and making the land more vulnerable to erosion. The movement of sediments

also affects the useful life of reservoirs.

Erosion occurs in virtually all Eco-regions. A number of Large Ecological Units (Figure Nº 9)

have been identified with critical erosion conditions. These include the western flank and the

13

upper and lower sectors of the Quebrada de Humahuaca; the Fluvio-lacustrine plain of Valle

Central de Tarija; the Sub-Andean Valleys, the banks of the Grande Tarija and Bermejo rivers;

the lower course of the Río San Francisco; El Ramal; the confluence zone of the rivers Lavayén

and Grande, La Almona; the valleys of Siancas and Perico; the piedmont of the Sierras de

Tartagal and of the Sierras de Maíz Gordo and Centinela. The location of these critical areas as

a whole reflects corresponding climatic and edaphic restrictions.

The occurrence of mass-movement processes is critical in the headwaters of the rivers Iruya,

Pescado and Quebrada de Humahuaca (2 and 31), and the presence of rills and badlands is

evidence of intensive processes of erosion in the Valle Central de Tarija. Critical erosion

situations are often found along the banks of rivers, especially in the upper basin. Some 13.35%

of the surface of the Large Units is affected by severe or very severe mass-movement

processes (Figure Nº 22a and Figure II of Annex II)

The processes of soil degradation (understood as degradation from misuse and overgrazing of

pastures, shrub lands or forests where the original vegetation remains but has been altered by

over-use), erosion and desertification, have been evaluated on the basis of the Ecological

Regions (31).

In terms of erosion, it may be noted that 52.3% of the basin presents conditions ranging from

significant to very severe, and only 47.63 % of the surface of the Large Units shows minimal,

restricted or insignificant erosion (Table N° 3 and Figure N° 17).

Desertification (figure n° 18) constitutes an indicator covering all the processes of degradation

of environmental conditions in arid and semi-arid areas, among which soil erosion and

vegetation destruction are especially important. The highest degrees of desertification in

Argentina are found in the peladares [barelands or denuded areas] of the Bermejo (figure nº

22b), and in the eastern andes eco-region, in the headwaters of the rivers and in the valley of

the Quebrada de Humahuaca and in the Semi-arid Chaco Eco-region, in the Subregion of the

Current Overflow Channels and Washouts of the Bermejo. In Bolivia, they occur in the fluvio-

lacustrine plain of the Valle Central de Tarija, where degraded areas cover more than 57% of its

area. Taken together, the sectors that show significant to very severe desertification represent

about 38.9 % of the total surface area of the basin, while 61.1% shows conditions of non

existing, minimal or limited desertification (table nº 3). In this respect, soil degradation through

the processes of erosion and desertification decreases the agricultural suitability of the basin.

Among the transboundary manifestations we may note:

Increased transport of sediments, with its impact on the active fluviomorphological dynamics.

While this phenomenon is primarily of natural origin, human intervention increases the

associated environmental conflict and affects the existing infrastructure downstream, the

processes of formation of the Delta of the Paraná and the navigation channels of the Río de La

Plata.

The SAP has been particularly interested in deepening understanding of the processes of

generation and transport of sediments, especially in Element 1.1 in both countries (2, 3, 4 and

14). The mathematical models used for the study show that the total of the material produced by

14

surface erosion alone and transported to the final section of the Upper Basin of the Bermejo

(Juntas de San Francisco) amounts to some 18,500,000 m3/year (corresponding to

49,000.000,t/yr), of which 64 % is generated in Argentine territory and the remaining 36 % in

Bolivia (2).

Table Nº 3

Total areas of the Basin affected by processes of

Soil Degradation, Erosion and Desertification

Problem

Degradation

Erosion

Desertification

Category

Area km2

%

Area

km2

%

Area km2

%

None

1,674

1.36

9,198

7.47

34,864

28.31

Minimal

12,903

10.48

26,262

21.32

13,084

10.62

Limited

32,920

26.73

24,472

19.87

27,342

22.20

Significant

54,793

44.49

36,232

29.42

25,892

21.02

Severe

9,164

7.44

26,174

21.25

11,786

9.57

Very severe

11,708

9.51

824

0.67

10,195

8.28

123,162

100.00

123,162

100

123,162

100

The processes of erosion and desertification to be found in the Basin reflect different natural

and man-made causes.

The amount of sediments (produced by all the processes of erosion, mass removal, etc.)

carried by the river as far as Juntas de San Antonio was estimated at 24,000,000 t/year,

corresponding to about 15,500,000 t/year from the Rio Grande de Tarija and 8,500,000 t/year

from the Upper Bermejo River. Expressed as quantities per unit of surface of the basins, the

figures amount to approximately 1,400 t/km².year and 1,700 t/km².year, respectively.

Using data from simultaneous records, between the station at Alarache, which covers

essentially the area corresponding to the Eco-region of the Eastern Andes, and the station at

Aguas Blancas, which covers 96% of the Upper Bermejo basin, we can obtain by subtraction

the amount of sediments generated in the Subandean Eco-region, at 2,539 t/km².year. This

same difference can be observed in the Río Grande de Tarija.

In terms of the impact of this problem on infrastructure, information is available for the Valle

Central de Tarija on the amount of sediments flowing into the San Jacinto reservoir, which is

more than 2,000 t/km².year (equal to a load of 1,697 m3/km2.year), calculated on the basis of

records for 1989 and 1995) (2). On the other hand, in the Argentine portion of the upper basin,

the specific solid flow in the Río Blanco reaches 3,743 t/km².year and in the Río Iruya, 14,869

t/km².year.

15

In comparative terms, according to estimates based on available records, about 80% of the

suspended load carried to the lower basin downstream Junta de San Francisco comes from the

upper Bermejo basin, and the remaining 20 % from the sub-basin of the San Francisco. In fact,

taking the series of solid measurements at Pozo Sarmiento - Zanja del Tigre (Bermejo) and

Caimancito (San Francisco), we obtain for the first an average figure for transport in suspension

of 70,508,100 t/yr (3,047 t/km².year), and for the second, 18,901,200 t/yr (720 t/km².year),

which gives a total of 89,409,300 t/yr (1.811 t/km².year). This value reaches 120 million tons

when we apply the solid/liquid flow ratio to that of average monthly flows.

In short, based on the period 1969-1989, we may say that the contribution of fine sediments

from the Bermejo River to the Plata system is about 100 million tons a year.

The intensifying migratory processes would appear to be another result of soil degradation and

the consequent loss of yields, increased production costs and declining standards of living,

which have produced or exacerbated socioeconomic imbalances to varying geographical scales

in the basin. This aspect is examined in greater detail in item 2.2.6.on the environmental

problem of Deteriorating human living conditions.

These impacts on productive and socioeconomic systems are reducing yields and living

standards for producers (especially small and medium-scale producers). This situation appears

to be one of the factors driving population movements (seasonal or permanent, domestic or

transboundary) especially among rural people. In Bolivia, there is a strong spatial correlation in

the Valle Central de Tarija between its status as a net source of migration and the degradation

of its soils. In this sub-basin, according to the surveys conducted (29), 42% of the population

has migratory experience, at some time for Argentina, and of this latter group 69.9% did so for

reasons of work. The surveys conducted in other areas of the Basin in Bolivia found figures of

the same order, and agricultural limitations were identified as one of the major causes.

Causes

The following are some of the direct causes determining the problem:

:

· The susceptibility of the geological substrata and geomorphological instability, where the

characteristics of the Eastern Andes and Subandean Ranges Eco-regions are particularly

restrictive. Occurrences of mass-removal and landslide were estimated in the studies on

sediments and division y ecological regions (2 and 31) and are shown in Figure Nº 22a.

· The characteristics of the soil itself, where 65.75% of the Basin's land area is classified with

use aptitudes of category VI, VII or VIII, are frequently associated with high susceptibility

and fragility because of structure, composition or slope.

· The

rainfall regime, and especially the tendency to torrential rains, that dominates the basin

as a whole.

· The strongly sloping topography, dominant in all of the Upper Basin (gradient map in Figure

V in Annex II) and geomorphological instability.

· Deforestation, where the area affected by massive deforestation for agricultural purposes

exceeds 26% of forest or cloudy cover. For the basin as a whole, nearly 23% of the Large

Units examined show evidence of deforestation, ranging from significant to very severe.

· Poor management of farm lands and overgrazing, such that 61.4% of the Large Units

16

into which the Basin was subdivided show situations of over-use, ranging from significant to

very severe. This numbers are coincident with data for the Bolivian sector, according to

which 60% of the pasture lands of the Eastern Andes show signs of overgrazing.

A general conclusion to be derived from these studies (2) is that there are no identifiable

management measures in the upper Bermejo River basin that would substantially affect the

quantity of sediments generated by the Basin as a whole. From this point of view, it may be said

that the most productive sediment zones in the Upper Bermejo River basin are not significantly

affected by human activity at this time.

This is not to say that specific local problems, related to sediment production at certain points in

the basin, cannot be dealt with by structural and/or non-structural measures designed for that

specific objective. In this respect, it would be advisable to examine in greater detail the

technical and economic possibilities for structural and non structural intervention in the drainage

networks of the valleys feeding into the Bermejo River, as well as possible techniques for

mitigating non point erosion.

Among the specific basic causes, the direct manifestations of which were discussed earlier,

are:

· Unsuitable use of the land, without considering its aptitude

· Unsustainable forestry and sylvo-pastoral practices.

These direct causes and basic specific causes affect the development of the basin, through

the loss of natural productivity, the reduction of the land's agricultural output capacity, greater

risks of crop and livestock failure, loss of productive areas, greater risk from salinization and

degradation of water quality and increased soil compaction from over-use, leading to the loss of

the soil's water retention capacity and greater susceptibility to erosion.

2.2.2. Water scarcity and availability limitations

Constraints on the development and exploitation of water and natural resources for sustainable

economic uses are related to natural fluctuations in the availability of water and in

fluviomorphological dynamics, associated with both seasonal and extraordinary factors, among

which we may point to the general scarcity of water during dry periods, both for human

consumption and for farming and livestock use, and low levels of production and economic

return. This latter aspect affects farmers who must compete with other economic sectors. As

well, the water shortage implies a heavy seasonal pattern to agricultural employment,

coincidental with the rainy period.

Annual or seasonal water shortages in various parts of the basin affect various natural and

human components in different ways. This problem makes itself felt most acutely in connection

with agricultural needs.

Under other criteria, this water shortage affects the reserves of water for human consumption,

and its availability for ecological processes such as vegetation growth and biological

productivity. With respect to the scarcity of water for human consumption, this affects a wide

area of the basin, and brings in its wake problems of public health and severe limitations on

17

development. In the arid and semi arid Subregions of the Eastern Andes (Figure Nº 21b) (such

as the Valle Central de Tarija and the Quebrada de Humahuaca) and the Subandean Eco-

region, as well as the Semi-Arid Chaco Eco-region, a high percentage of the rural population

has no access to safe drinking water. This deficit becomes critical during the dry season, when

human living conditions decline: (20) has analyzed the importance of limited water resources as

one of the environmental and socioeconomic factors that restrict the adoption of sustainable

development practices in the lower basin. Some 31% of the basin's surface area is affected by

severe or very severe conditions of water shortage during the dry season (nearly 38,000 km2).

The average annual flows in the rivers of the Eastern Andes and Subandean Eco-regions show

wide fluctuations. The Bermejo River at Juntas de San Antonio, the last point in Bolivian

territory, has an average annual flow of 220 m³/s, of which 92 m³/s corresponds to the Upper

Bermejo and 127 m³/s to the Grande de Tarija rivers; with specific flows of 18 and 12 l/s.km²

respectively. Upon leaving the Upper Basin, after Junta de San Francisco, the Bermejo river has

an average annual flow of about 480 m³/s. If we look at flows during the dry season, in the most

critical month (generally September), the Bermejo River at Juntas de San Antonio has an

average monthly flow of 19 m³/s and at Junta de San Francisco the minimum monthly flow is

about 30 m³/s.

These magnitudes constitute the available water in the Lower Basin, which includes an

immense plain where soil and climatic conditions are favorable to the growing of a wide variety

of crops, and where the fundamental limit on development is the reduced availability of water.

The transboundary manifestations include the following:

The growing population in the Bolivian portion of the basin means that the water shortage is

growing, and placing increasing pressure on migration as a transboundary manifestation, both

seasonal and permanent as a consequence of restrictions on the permanent use of available

agricultural land.

These shortages and restrictions on the exploitation of water resources can ignite or exacerbate

conflicts over the use of surface and underground water, seasonal or permanent, especially in

the areas where the water shortage is most severe, in the upper basin and in the Eco-region of

the Semi-arid Chaco. The lack of understanding of existing resources makes it more difficult to

assess the conflict and propose solutions. Shortcomings in legislation and organizational

weaknesses (24 and 26), together with a complex institutional framework that is inadequately

articulated and organized with respect to management of the basin, make it difficult to forestall

such conflicts. The low incomes of the local population, reflecting restrictions on the use of

water resources and the uncertainties of seasonal employment, are producing population

movements both within and beyond the basin. It is to be noted the temporary migration of

people seeking to complete year round employment, which otherwise is concentrated in the

rainy season.

Causas

The difficulties in exploiting water resources are linked to a number of causes.

The direct causes include:

18

· Climatic limitations owing to increasing seasonal variations (from east to west), the inter

annual variability and the scarcity or deficit of precipitation, which reflects on the hydrological

regime. It should be noted that the summer (December - March) is the time of maximum

flow, when 85% of the run-off from the upper basin in Bolivia occurs, while the flow is

exhausted from April to September, posing a severe limitation to productive use.

· Flow restrictions, which become progressively more severe as one moves from the Eco-

region of the Sub-Humid Chaco to the west, where during the dry season there is a

generalized water shortage for both human consumption and agricultural and livestock use.

For example, at the Juntas del San Francisco, the mean annual flow of the Bermejo can

drop from 480 m3/sec. to a monthly minimum of around 30 m3/sec. The water shortage

(Figure Nº 21b) is a dominant fact of life in the Eco-regions of the Semi-Arid Chaco and in

the Eastern Andes, where the situation is critical in the Valle Central de Tarija and in the

Quebrada de Humahuaca.

· High sediment content in the water system, which reaches concentrations exceeding 10

kg/m3. In addition to the issues discussed in item 2.2.1, sediment can be considered as a

factor limiting the aptitude of the water resource (for human and agricultural use) and as

responsible for the rising costs of maintenance and the declining useful life for infrastructure.

· High fluviomorphological dynamics, which work through processes (such as undermining

of river banks, cut off meanders, overflow or change of channels) to damage, destruction or

loss of efficiency of water-capture infrastructure.

· Local depletion of the water table

· High salt content. In Bolivia, the assessment of water quality from the viewpoint of its

suitability for irrigation shows that of 20 sites sampled, 17 showed medium salinity (without

restrictions), 2 were highly or very salinated, and only 1 showed low salinity (according to the

classification of the Soil Conservation Service-USDA). On the Argentine side, there are

frequently use restrictions due to the concentration of salts in underground waters. The

localized presence of arsenic and other minerals (of natural origin) in underground waters,

well above quality standards, has been recorded in the Eco-region of the Semi-Arid Chaco.

· Relief limitations. In the upper basin, the valleys are narrow and slopes are steep, giving

rise to torrents that carry massive deposits of course sediments. This limits the possibilities

of regulating and diverting the flow. In the lower basin, the fluviomorphological dynamics and

the weak energy afforded by the relief are factors restricting use of the resource.

· Inadequate hydric infrastructure, which fails to offset or mitigate the climatic limitations

discussed above, or those deriving from present or past processes of soil degradation. This

is frequently aggravated by inefficiencies in water management or applied technologies as

well as by "irrigation culture" shortcomings of the users.

Among the specific basic causes we may cite

· Inefficient exploitation of water resources and low utilization of the existing potential.

In Bolivia, current exploitation of the Bermejo and Grande de Tarija rivers is limited to

irrigating small fields, and to human and livestock consumption. Based on current use

patterns, demand is estimated at approximately 110 hm3/year, less than 2% of the available

volume; in other words, exploitation is not significant. Yet toward the end of the dry season,

this level of exploitation consumes virtually 100% of the available flow in rivers of the

Eastern Andes, especially in the sector corresponding to the Valle Central de Tarija (where

most of the population and the irrigated farming is concentrated) and where there is only one

19

man-made flow regulator, the San Jacinto dam (on the Tolomosa river) with a useful storage

capacity of 48.7 hm3. The cultivated area under irrigation is 2% of the Bolivian portion of the

basin. In the Argentine sector, the exploitation of water resources focuses on irrigated

farming and water supply for human and livestock consumption. The most recent census

data available (1988) show that in the Argentine basin, only 6 % of agricultural land was

devoted to crops. There are a few examples of more intensive exploitation. In Jujuy, the

level of water resource exploitation is high, thanks to the reservoirs of Las Maderas and La

Ciénaga. Together with the Los Molinos dam on the Río Grande they supply irrigation water

to the Valle de los Pericos, in addition to providing water for drinking and for electricity

generation. In Salta there has been a major expansion of the area under irrigation, and its

water sources are fully committed. In the Upper Basin in Salta and Jujuy piedmont runoff

supplies local irrigation systems. In the Lower Basin, water is drawn for irrigation and human

consumption (e.g. the Laguna Yema system, in Formosa), and there are in fact some major

irrigation works, privately owned, such as in the rice-growing area now being developed in

the Chaco. The cultivated area under irrigation accounts for about 4% of the Argentine

sector of the Upper Basin, and 2% of the Lower Basin. (1 and 37).

· Inadequate understanding of the supply and usable potential of surface and

underground waters. In this respect, (2) and more particularly (23) have made progress in

systematizing and understanding the functioning of the system, in order to establish the

hydrometeorological and hydrosedimentological component of the Environmental

Information System for the Bermejo River Basin, as an input for policy definition and

resource use planning. There also is a need to improve the understanding of underground

water resources.

· Inadequate financial resources for implementing existing water exploitation projects for

irrigation and other uses.

· Low levels of output and economic return. Low intensity of agricultural use in general,

little or no land devoted to agroindustrial crops (Figure Nº 14). This latter aspect affects

farmers who must compete for water rights with other economic sectors. The impacts

include current and potential inter-jurisdictional conflicts among the different users in a

region, and effects on health that are contributing to unsustainable development in the

basin.

· Inadequate legal and institutional framework for handling and managing water resources (24

and 26).

2.2.3. Degradation of water quality

At present, stretches of the watercourses are affected by pollution from rural activities, and this

is made worse when the water passes through towns and major cities. Indeed, some stretches

of the rivers show significant organic and bacterial pollution from the dumping of agricultural and

industrial wastes, and from poor livestock management.

Transboundary manifestations include:

The transport of organic and microbiological pollutants and other agents of sanitary significance,

of urban and industrial and even agricultural origin. The trend here is rising. The impacts of this

problem include: direct degradation of water quality, risks to human health, damage or loss of

riparian flora and fauna and fish mortality in the most critically polluted situations, loss of

biological productivity in aquatic communities (both lotic and lentic environments) and shoreline

20

communities, effects on the uses of water resources, and increased costs of treating water for

domestic or productive consumption.

All of these aspects have both direct and indirect transboundary manifestations. The indices of

organic pollution in frontier rivers are fairly high, but they affect only short stretches, and the

problem is significantly attenuated by the effect of dilution. While organic, bacterial and

industrial contaminants are localized at specific points in the basin, there is a potential and

growing risk if adequate prevention measures are not taken. If the situation worsens, this would

affect both countries, and other basins downstream. Physical pollution, which appears during

the wet season in the form of high sediment concentrations, is the most significant

transboundary manifestation, since the massive transport of sediments affects water use both

within the basin and beyond it, into the Paraná - Río de la Plata system.

Among the direct causes we may cite:

· Degradation of soils and erosion. The impact of sedimentation on water quality has

already been examined in item 2.2.1. As an example, we may note that the concentration of

sediments in the water system can exceed 10 kg/m3. Related to this problem, and also to

that of water quality, poor water management has led to salinization of the soil that has

reached severe proportions in the following areas: terminal overflows in Bañados del

Quirquincho, the terminal portion of the Itiyuro alluvial fan, areas around Rivadavia and the

headwaters of the Río Guaycurú, accounting for about 7% of the basin's total surface area.

· Dumping of raw or semi-treated sewage from populated centers. Industrial pollution at

some points in the basin. Pollution from improper livestock and agricultural management.

Water pollution in several stretches of the river results from the dumping of urban and

industrial wastes, draining of residual agricultural chemicals, leaching of salt and sediment

transport. This environmental problem reaches critical proportions a) locally, through

organic and bacterial pollution and salt content in the dry season (April to December), when

river flows are at their lowest, and b) regionally, because of the high sediment content during

the rainy season (January to March).

In Argentina, sampling conducted to examine the water quality situation for the basin as a

whole show that, of 14 control points, 6 present some type of use restriction, due in all cases

to bacterial contamination (total and fecal coliforms), frequently compounded by excessive

concentrations of iron or sulfates. Readings exceeding permissible guidelines for Total and

Fecal Coliform Counts, which imply restrictions on human consumption (with conventional

treatment) and on recreational activities have been found in the San Francisco river, when

crossing Provincial Highway N° 15, in the Bermejo river when crossing Provincial Highway

N° 34 in Salta; the Los Molinos Dam, the Grande river in Las Lajitas, the San Francisco

River in El Piquete and the San Francisco river in Jujuy. In Formosa and Chaco, studies

show that permitted levels of total and fecal coliforms have been exceeded at the sampling

stations for Bermejo (Teuco) river, in El Sauzalito and in Puerto Lavalle. The problem of

water quality was dealt with in (22), particularly in its relationship to the design of a

Hydrometeorological and Water Quality Network, a component of the Environmental

Information System for the Bermejo River Basin.

In Tarija, Bolivia, according to current legislation, the following stretches have been identified

as unfit for human consumption (Level D)6 with conventional treatment: in the Río

6 Criteria contained in legislation (Law 1333, Bolivia).

21

Guadalquivir from the locality of Tomatitas to the confluence with the Camacho river, in the

Camacho river from the locality of Chaguaya to the confluence with the Guadalquivir river ,

in the Salinas river from the locality of Entre Ríos to La Cueva, in the Grande de Tarija river

from the confluence of the Quebrada 9 to the confluence with the Bermejo river and in the

Bermejo river from the monitoring station at Aguas Blancas to the confluence with the

Grande de Tarija river. The stretches where water is only fit for human consumption with full

physical and chemical treatment (Level C), are: in the Tarija river from the confluence of the

Camacho and Guadalquivir rivers to 30 km downstream, in the Chiquiacá river from

Chiquiacá Norte to Chiquiacá Sur, in the Itaú river from Itaú Norte to 13 km downstream of

the community of Aguas Blancas and the stretch of the Bermejo river between Emborozú

and the city of Bermejo.

By way of reference (complete data in Annex II), of 41 control points analyzed in the

Bolivian sector of the Bermejo River Basin, 28 showed some degree of contamination

(essentially from bacterial or organic materials).

The specific basic causes include the following

· Inadequate or unenforced environmental standards. It was shown that legislation is

asymmetric, incomplete or lacking in the area of protecting shared resources (water in

particular and natural resources in general), managing urban and industrial wastes

(incomplete) and the environment as a whole (asymmetric rules), and there were also

difficulties (such as organizational weaknesses) in enforcing regulations. To this must be

added inadequate or non-existent legislation on management instruments, or the lack of

regulations, which makes them unenforceable. The need for inter-institutional coordination in

environmental management and for integrated management of the basin was made clear in

(24 and 25).

· Inadequate sanitary infrastructure and weaknesses (primarily financial and others) of

the institutions responsible for administering sanitary infrastructure systems. This is

clear from the high proportion of the population that has no access to drinking water or

sanitation services, and the lack of procedures for final disposal of urban and industrial

wastes. In the Argentine sector, 47% of dwellings in the basin as a whole were found to be

deficient7. The most critical situations are to be found in departments with a very high

proportion of families living in deficient housing (over 70%). These are, by province: Iruya,

Santa Victoria, Rivadavia, La Caldera and Anta, in Salta; Bermejo, Patiño, Matacos, Laishi

and Pirané, in Formosa; Valle Grande, San Antonio, Santa Bárbara, Tumbaya and Tilcara,